Beyond a Land Acknowledgment

Article by Angelina Oliva

Have you ever thought about the land you walk on and what was here before?

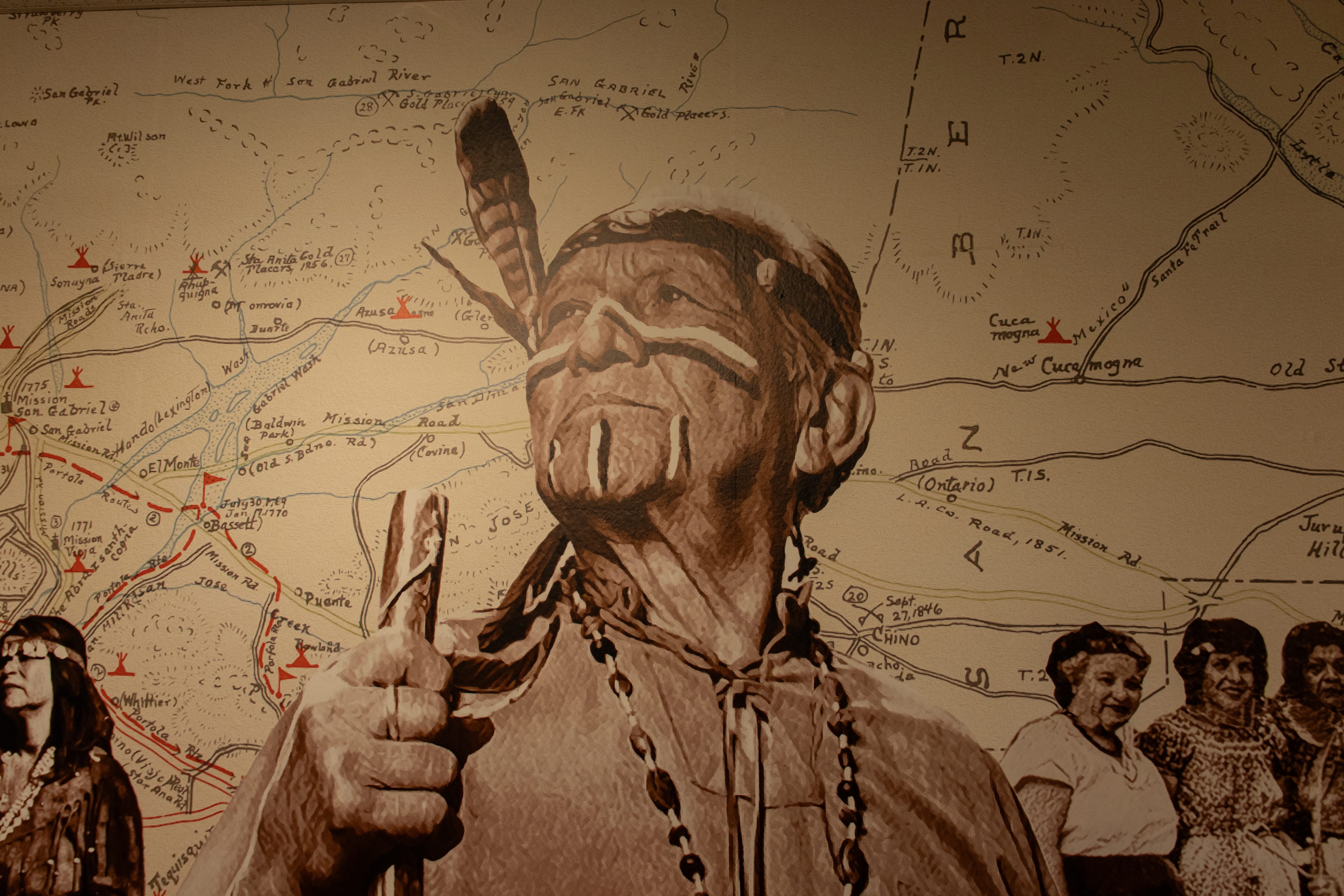

Long before the paved walkways and glistening glass doorways of the Citrus College you know, was the vast land of the Los Angeles Basin. Indigenous people roamed from the hills to the shores. The people that took care of this land were the “Kizh” people. Named after the homes that they built. Natural resources, such as tar from La Brea tar pits, were used to create these homes.

The Kizh tribe has a rich history but oftentimes history is written by the victors. History can be rewritten and manipulated. It is so important we tell the true story of the past.

“Their legacy was always to tell their stories to keep their history alive through us,” Andrew Salas, the Chairman of the Kizh nation, said. His parents, grandparents, and ancestral lineage can continue because these stories are shared. The history needs to be known. Even things such as tribal names can be shifted for the gain of one group and oppression of another.

The arrival of Spanish colonizers changed the way in which the Kizh lived, even down to what they were called. The Spanish called these indigenous people “Gabrielelnos.” This land became known as El Valle de San Gabriel, which in English is San Gabriel Valley. The San Gabriel mission was built on this land by the enslaved Indigenous people.

The San Gabriel mission was a terrible place for Indigenous people. It was filled with sickness, murder, and rape. This was a genocide. Salas’ family was able to survive because they were taken away from the mission and were servants to the prominent families at the time. This same thing happened when the Mexican government took over. Once more when the American government was established.

“Decade after decade after decade, for over 200 years, our families, Indigenous people, were just transferred over and being mixed with the prominent families that came to establish themselves in our homelands,” Salas said. “That’s why we survived here.”

Indigenous communities have been able to survive for centuries, yet they were not legally citizens until 1924. The U.S. Congress passed the Indian Citizen Act one hundred years ago. Not until 1994, did the Gabreleno tribe become state recognized. They are still fighting for federal recognition.

The state proclamation of California was addressed to the Gabrieleno tribe. Citrus College’s land acknowledgment addresses the local tribe as Gabrelino-Tongva. But the tribe addresses themselves as Kizh. There are many names that have been put upon this tribe, which makes it hard for people to know their true history.

As mentioned, Gabreleno came from the Spanish and Kizh came from the homes built. Where did Tongva come from?

In 1903, a man named C. Hart Merriam was made to research the Indigenous people of the Los Angeles basin by the Berkley family. He was a biologist not a historian. Merriam went to talk to Indigenous people in the San Gabriel area. This happened before Indigenous people were given citizenship, so no one wanted to talk to him for their own safety. He was then directed to the Fort Tejon reservation. This reservation was established by Benjamin D. Wilson of Mt.Wilson. Wilson was an agent for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and he put Indigenous people from San Gabriel into that reservation. Merriam was able to speak to someone that descended from San Gabriel, Jesus Haro. Haro was born close to the mission near a village called “Toviscanga.” Merriam could not pronounce this name so he abbreviated this name to Tongva, Salas said.

How did the name get reestablished?

“The Tongva term was implemented by individuals,” Salas said. “They had an agenda, and they wanted to use real Indians to help with their agenda, without telling us what their agenda was.”

Merriam’s notes were published by the University of Berkley. People in academia used the Tongva term from his notes to establish a new foundation. In 1994, the Tongva Springs Foundation was established. There are natural springs near UCLA and they wanted to protect those springs from turning into a plaza. Salas’ father Ernie P. Teutimez Salas helped fight for the preservation of the springs. They were able to protect the springs and Ernie Salas was given a symbolic key for the springs.

“That was the first time Gabreleno got their land back,” Salas said.

Although this was a stride in the right direction, people in academia took advantage of this occasion. The foundation promised to help the tribe gain recognition, under one condition, being called “Tongva.”

“We didn’t want that name,” Salas said. “Little by little, these individuals took out the name ‘Spring,’ ‘Foundation,’ and they put Gabrieleno/Tongva tribe.”

The Citrus College land acknowledgement, uses this name Gabrieleno/Tongva to address the local indigenous tribe to this day. Citrus College has this land acknowledgment to dedicate and give an insight into the history of this land and the people who lived on the land. Even though the land acknowledgement recognizes indigenous people, is it enough?

Citrus College’s land acknowledgment is published online. In recent years, there have been land acknowledgments given during graduation.

“The land acknowledgment that was given last June during commencement was developed by our Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility + Committee,” Dr. Greg Schulz, Citrus College President, said. “This is a newer committee at Citrus College established in 2022. The Committee has 30 members, with representation from students, faculty, and staff.”

This long acknowledgement is two years old. It is still new for Citrus College. This document has fluidity according to Dr. Schulz. It can adjust to what the Indigenous communities point out.

What can be done beyond a land acknowledgment?

From 2017 to 2019, Citrus College held annual powwows. A powwow is an Indigenous ceremony that includes food, singing, and dancing. Tribes from all across California were invited. The student group that organized the event went by both the Indigenous Student Association and the Native American Student Association.

“My impression of the real motives for the students was that they wanted to celebrate their own heritage and culture,” Brian Waddington, the ISA faculty advisor, said. “But also raise awareness of native culture, First Nations culture here on campus.”

In addition to these powwows, there would be other events on campus to promote Native American culture. There was Red Dress Week, to raise awareness of murdered and missing Indigenous women. Singers, drummers, and speakers were also brought to share their stories and culture on campus.

“I think the best thing for students is hiring more Indigenous educators and having that specific voice on campus,” Isabella Reyes, the ISA president, said. She feels it is important to bridge the gap between faculty and students.

The current number of employees that categories themselves as “American Indian/ Alaskan Native” is seven. The current number of “American Indian/ Alaskan Native” students is 35. These are based on self-identification during the employment application and enrollment application process.

A recent step that Citrus College has taken to ensure Indigenous voices be heard is the development of Employee Resource Groups.

“One of the Employee Resource Groups is designed for Indigenous American employees,” Dr. Schulz, the superintendent and president of Citrus College said. “This group will have the opportunity to provide guidance and recommendations on the land acknowledgment, future activities, and partnerships with local tribes.”

Having these groups allows for Indigenous faculty members to speak their truth. Students should have this same outlet. The ISA was that group.

Native youth may feel lost or disconnected from their cultural identity. Reyes didn’t feel like she could find her identity until college. “It wasn’t until I got to college, the (ISA) board really introduced themselves to me, and I think that was the first time I experienced that kind of kindness.”

Going through college and life can be quite lonely. Students may have financial instabilities or even be the first in their family to go to college. Having groups like ISA allows students to have other people to lean on in this complex academic journey.

Awareness of the Native community is necessary to show that they still exist and have voices that need to be heard. The presence of ISA provided that space for students to have community. Events like the powwows gave a reason for the community to come together. All these events, as well as the rest of the country, were brought to a standstill once the quarantine of 2020 happened. As restrictions started to lift, students started trickling back onto campus. Unfortunately, the ISA was one of many groups that ceased to exist at Citrus College. In order to bring back these clubs students need to participate.

“To encourage more student involvement in bringing diversity to our campus, the office of Student Life and Leadership Development continues to work with student leaders to develop and promote diversity initiatives such as supporting the formation and growth of various cultural clubs and organizing regular events that celebrate various cultures and identities,” Dr. Schulz said.

Diversity and inclusivity are important to have for the Citrus College community. Student participation is needed to bring back festivities, such as powwows, and other community-building events. This will not only bring awareness to native culture, but it will also bring representation for native students on campus. Having groups of other Indigenous community members can help native students feel one with their culture. Indigenous youth should be able to feel part of their culture especially since many native cultures have been lost in time. Destruction and assimilation of Indigenous ancestry have made it difficult for young people to learn about their cultural identity. Citrus College could be a part of uplifting the next generation of Indigenous youth. But how? By connecting past generations and future generations together.

What can Citrus College do for future community building with Indigenous tribes?

“I think it’s powerful to create a campus space and climate where people feel like they can lend their voice, and their voices will be considered,” Dr. Schulz said. “And we talk about that in our leadership team, because in our effort to continually try to create a climate where all of our students have a sense of belonging. They feel welcomed and supported here and our employees, that can be one of the things that help us ensure that.”

Indigenous voices must be heard to create change both from the community on campus but also the Indigenous community itself.

“Research the truth,” Salas said.

To move forward in progress you must know the true history. Speaking about the real, gritty, ceremonious, even at times uncomfortable history is necessary to grow and make sure future generations don’t turn their backs and move backward. We must tread forward by telling these stories and creating a strong community.

“Wherever you go in this life, you’re not alone,” Reyes said. “Every step you take, thousands and thousands of ancestors walk with you and they see you. They’re going to do everything in their power to help you in that way. Just have that faith and keep going.”

What Chairman Andrew Salas says in this article is about …researching the “TRUTH “…without the truth and accepting history at face value is WRONG

Please understand…documents and all that is needed to prove Kizh Gabrieleno Indigenous people is readily available …..

There’s no other way….please help us …. Research and know the Truth not what the pretend Indians are feeding all…..false history

GER IT RIGHT people please!!!